A lawsuit filed on behalf of neighbors to prevent the demolition of No. 1 St. Mark’s Place was presided over by a Superior Court judge, ending a two-year rift that pitted independent landowners against a corporate behemoth — all over 8-feet of land. Another battle for the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation? Not this time; this took place in May of 1856.

READ FULL ARTICLE: http://www.thevillager.com/?p=1332

Saturday, December 31, 2011

Eric Ferrara's St. Marks Place article in The Villager

Monday, December 19, 2011

Old Ad: Hiram Anderson's "Great Carpet Establishment"

Inside Hiram Anderson's Great Carpet Establishment at 99 Bowery (c.1858), which billed itself as the “largest carpet establishment in the U.S.”

Today 99 Bowery hosts the Chinese-owned Olivia Furniture Corporation.

Friday, December 16, 2011

On this day, December 16, 1848, the prestigious Park Theatre closed

|

| The Park Theatre, located just below the one-time fashionable Chatham Square, was one of the nation's first contemporary professional theaters. |

Opened on January 29, 1798, the Park Theatre was built to satisfy the city's Post-Revolution aristocracy and elevate New York City's status on the world stage as a culturally and commercially viable metropolis. Early planners set out to create a megalopolitan empire on par with European cities like Paris and London, attracting some of the wealthiest families of the era to Lower Manhattan -- and the Park became the crux of this Utopian-seeking high society.

The theatre offered world-class acts from around the globe and was the first to introduce professional Italian Opera to the country in November of 1825, Rossini's "Il Barbiere di Siviglia" (The Barber of Seville). The Park became the premiere playhouse for U.S. debuts of European superstars such as Norwegian violinist Ole Bull and Austrian ballerina, Fanny Elssler and was a breeding ground for pioneers of early American theatre as some of the most celebrated actors, singers, dancers, playwrights and producers of the 19th century earned their reputations at the Park.

Despite the high caliber of performers and pedigree of theatre-goers, the Park's function was wholly utilitarian and lacked any aesthetic beauty. It was described as "an unattractive auditorium, inadiquately illuminated, with many uncomfortable seats." by The Magazine of history with notes and queries, Volume 22.

|

| The Bowery-Theatre, 46-48 Bowery |

By that time, New York City had changed dramatically. It went from Colonial backwater to cosmopolitan city in a matter of decades and the rapid change did not sit well with the entire population, as explained in The Bowery: A History of Grit, Graft and Grandeur:

As grand as (the Bowery Theatre) was, a new theater in Manhattan was not welcomed by everyone. Much of the conservative population was not adjusting well to the new cosmopolitan status of New York City and the hedonistic culture it bred. An 1826 Magazine of the Reformed Dutch Church article warned: “A theatre in this city was opened for the season on the Monday evening of last week. We do not mention this fact to give information;—we mention it to excite Christians to pray against the wide-spreading pestilence; to exhort Christian parents to keep their children from the vortex of destruction.”

The Christian Spectator commented: “The influence of the theater is bad, and only bad,” along with several more paragraphs of colorful passages like, “The theater cannot be reformed. We should just as soon think of reforming the devil himself.”

However, it wasn’t theatrics per se that had conservatives up in arms, though they did complain of productions that were lowbrow, amoral and obscene. It was the alcohol, prostitution and gambling that went hand in hand with a night on the town in the 1820s and ’30s that really bothered them. For example, it was common practice for theaters to hire prostitutes from nearby Five Points to work the upper tiers of the auditorium, and liquor was served by waitresses of questionable morals who wore dresses that revealed their ankles.

| ||||

| Early Bowery Theatre ad promising "Piracy Mutiny & Murder," and "Fire Worshipers." |

While the Park continued to offer top-notch European artists, the Bowery promoted home-grown entertainment and stole some of the Park's thunder for a few years, however the Park remained a celebrated New York City treasure until its demise.

The original 1798 Park Theatre burned to the ground in 1820 but was rebuilt by 1821, only to suffer the same fate on December 16, 1848. Some hanging playbills were ignited by a nearby gas lamp and within an hour the structure was devastated. It was never rebuilt, ending half a century of cultural influence.

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

Carlo Tresca's "Il Martello" first published today, December 14, 1917

|

| An April 1920 cover of Il Martello, published at 208 E. 12th Street |

Called "radical" and "subversive" by opponents, Il Martello faced tough government scrutiny for its anti-war, anti-establishment views and was deemed "unmailable" at the time by the U.S. Postal Service.

The newspaper, originally titled, Il Martello: Giornale politico, letterario ed artistico ("The Hammer: Political, Artictic and Literary Newspaper"), was founded in in November of 1916 by a man named Luigi Preziosi. Tresca purchased the magazine for a few hundred dollars in late 1917, soon after halting operations of his previous journal, L'Avvenire ("The Future") in August of that year.

Tresca purchased Il Martello -- but did not attach his name to it for over a year -- as a way to circumvent government censorship. By the time he acquired the newspaper, Tresca's involvement in national labor movements and progressive writings had caught the eye of authorities, who went as far as tapping his phone line.

|

| Carlo Tresc |

According to Carlo Tresca: Portrait of a Rebel by Nunzio Pernicone,"Tresca's acquisition of Il Martello demonstrated his skill in the fine Italian art of arrangiarsi -- to manipulate a situation for the best outcome."

Knowing he could never get the proper permits to publish in his name, Tresca essentially used Il Martello as a front to continue his mission; It was not until June of 1918 that his name appeared as publisher.

Il Martello moved into an office at 208 E. 12th Street by the Spring of 1920, and Tresca lived in an apartment above John's Italian restaurant at 302 E. 12th Street. Over the following twenty-three years, the publisher created a lot of enemies as an outspoken critic of Communism, Stalinism and Benito Mussolini's attempt to organize fascist support on American soil.

Ultimately, Tresca was assassinated on a Fifth Avenue sidewalk on January 11, 1943. His murder remains unsolved though several theories have circulated since the incident. One leading theory hints at Mafia involvement -- more specifically, Bonanno underboss Frank Garafolo, who at the time operated a Cheese import shop at 176 Avenue A, according to Manhattan Mafia Guide by Eric Ferrara.

Tuesday, December 13, 2011

New schedule, revamped "Lower East Side" and "East Village" walking tours

We are pleased to announce that our staple "Lower East Side" and "East Village" walking tours have been revamped with with a new route, content and guide -- author and director of Lower East Side History Project, Eric Ferrara.

Ferrara, a fourth-generation Lower East Sider, offers a decade of active research and over a century of ancestral community insight, providing a one-of-a-kind experience suitable for any casual tour-goer or hard-core academic.

Utilizing rare maps, photos, documents, articles and oral histories not found elsewhere, Ferrara digs deep into the neighborhood's forgotten history -- far beyond the familiar "immigrant experience" narrative -- exposing the social, political and cultural intricacies which made this so district vital to the evolution of our city.

Lower East Side Walking Tour

Every Saturday at 12:00pm (beginning January 7, 2012)

http://leshp.org/walking-tours/117-lower-east-side-walking-tour

East Village Walking Tour

Every Saturday at 2:00pm (beginning January 7, 2012)

http://leshp.org/walking-tours/61-east-village-walking-tour

Thursday, December 8, 2011

Map: Churches of the Lower East Side, 1877

|

| Click for larger map |

|

| Old St. Patrick's today |

A few of these original churches have been transformed into synagogues since 1877, including the First German Baptist Church (1) which has been home to Congregation Tifereth Israel since the 1960s and the Bialystoker Synagogue, which moved into the landmarked Willet Street Methodist Episcopal Church building (13) in 1905. Another example is the St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church (38), which lost much of its congregation in the 1904 General Slocum disaster and sat empty for decades until the Sixth Street Synagogue moved in just before WWII.

|

| Bialystoker today, 7 Willet St. |

If you would like to learn more about our local houses of worship, you may be interested in our seasonal Sacred Spaces walking tour of the Lower East Side.

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Industrial Lower East Side, part 2: The 11th & 13th Wards, 1891

For well over a century, the Lower East Side's waterfront hosted Manhattan's primary industrial district. Among dozens of factories and horse stables was one of the largest concentrations of coal, lumber and iron yards in the city. This map illustrates some of the larger companies operating by 1891, in the 11th and 13th Wards of the Lower East Side.

See "Alphabet City" in 1891: http://evhp.blogspot.com/2011/12/industrial-alphabet-city-1891.html

Tuesday, December 6, 2011

"Perambulating Fountains" of the Lower East Side

|

| Source: Directory of New York Charities, 1900 |

You are probably asking yourself, "What on earth is a 'perambulating fountain'?"

|

| Source: Directory of New York Charities, 1900 |

Before refrigerators, running taps in every apartment and public fountains -- let alone bottled water -- there were horse-drawn wagons that toured the local slums during summer months, offering free ice and water to overheated citizens.

The first cart embarked on June 15, 1891, paid for and organized by the Moderation Society, a temperance-advocating charity organization founded on the Lower East Side in 1879.

|

| Source: nycgovparks.org |

It took the Moderation Society eleven years to secure the proper permits and political support to launch the water wagon initiative, which was paid for by donations to the organization.

|

By the 1910s, pro alcohol-abstinence organizations like the Salvation Army began what were essentially marketing campaigns -- highly publicized "water wagon parades" -- with the goal of recruiting "boozers" to "get on the wagon" (meaning, exchange booze for water).

A new American catch-phrase was adopted from campaigns like these; those who made pledges to quit drinking were considered "on the water wagon." And those who returned to alcohol were said to have "fallen off the water wagon" (since shortened to "on the wagon" and "off the wagon.")

Sunday, December 4, 2011

How crowded was the Lower East Side?

In the decades following the Revolutionary War, opportunists from across the globe poured into New York City seeking fortune in the Capital of the newly formed United States of America.

Anticipating a major growth in population, the modern day street grid was established in 1811, opening up two-thirds of previously uninhabitable Manhattan real estate. As industry boomed, the city (perhaps conveniently) opened its doors to laborers, Irish and German immigrants, former Southern slaves, and down-on-their-luck job seekers.

Many successful families migrated north, away from the heart of the commercial and industrial districts and a class-structure emerged in New York City for the first time -- exemplified by this 1864 illustration:.

|

To give you an idea of how dense that is, today there is an average of about 70,000 residents per square mile in Manhattan.

Overcrowding eased up early in the twentieth century when the city subway system (1908), Williamsburg Bridge (1903) and Manhattan Bridge (1909) opened, allowing entire communities to relocate and move freely between Manhattan and the outer boroughs.

Saturday, December 3, 2011

Industrial Alphabet City, 1891

|

| Based on 1891 G. W. Bromley map |

By WWII most of these industries died out or relocated to the outer boroughs and the entire district was redeveloped during a post-war public housing initiative. Today "Alphabet City" is overwhelmingly residential.

Friday, December 2, 2011

Rare photos of the legendary Steve Brodie

These are some rare images relating to Steve Brodie, a man whose claim to fame was just that, a claim, that in 1886 he jumped from the Brooklyn Bridge and survived.

The following an excerpt from The Bowery: A History of Grit, Graft and Grandeur:

Brodie, a native Lower East Sider, was an outgoing, blusterous youth who earned the nicknames “Napoleon of Newsboys” and “George Washington of Blackbooters” because of the influence he had over other boys in the rowdy Fourth Ward. (Think Christian Bale in the 1992 movie-musical Newsies.) In one 1879 interview, sixteen-year-old Steve Brodie bragged about how he and other local “newsies” would band together to chase new competition out of their territory and complained about how Italians were taking all the bootblacking jobs.

A professional gambler as a young adult, Brodie fell into debt when he took on a dare to jump off the New York City landmark for $200—just months after daredevil Robert Odlum was killed while attempting the same stunt. As Brodie began to take full advantage of the publicity around his planned jump, a liquor dealer named Moritz Herzber offered to finance a saloon in Brodie’s name—if he survived.

On the morning of July 23, 1886, Brodie stood on the railing of the bridge while a couple of friends tested the waters below in a rowboat and news reporters gathered on a pier nearby. At 10:00 a.m., Brodie’s team called off the jump, claiming the tide was too strong. Brodie came down from the structure only to return about 2:00 p.m. that day,, when it is claimed he rode in the back of a wagon until he got about one hundred yards over the bridge, at which point he took off his hat and shoes and plunged over the railing into the East River.

Despite several “eyewitnesses” and lengthy news reports, most historians believe the jump was a hoax, theorizing that a friend threw a life-size dummy from the wagon that people mistook for Brodie amidst all the excitement. Brodie was arrested after being “rescued” from the water, but charges were dropped and he became an instant celebrity. Herzber made good on his promise, and Brodie’s saloon was opened at 114 Bowery. It also doubled as a museum dedicated to the stunt.

The public could not get enough of Steve Brodie, who went on to tour the country in vaudeville musicals Mad Money and On the Bowery, re-creating his famous leap for clamoring fans. Eventually, Brodie settled in Buffalo, New York, where he died from diabetes in 1901 at the young age of thirty-nine.

Steve Brodie’s stunt inspired a slew of pop culture references, including the 1933 Hollywood film The Bowery, in which fellow Lower East Sider George Raft portrayed Brodie in the lead role; and a 1949 Looney Tunes cartoon named Bowery Bugs, which re-imagines Bugs Bunny being the motivation for Brodie’s jump. The urban legend also inspired a popular saying: “pulling a Brodie.”

Thursday, December 1, 2011

210 E. 5th Street , Then & Now

210 E. 5th Street in 1892 (left), and today (right)

For close to half a century, this address hosted one of the city's most important union halls, Beethoven Hall. Between the late 1880s and late 1930s, several prominent organizations held meetings here: From the ILGWU and Federation of Labor, to the International Brotherhood of Teamsters and Jewish Socialist League of America.

Many high profile union leaders and politicos made rousing speeches here: from Emma Goldman and Johan Most to William Randolph Hearst.

Beethoven Hall played an important role in the Women's Suffrage movement and most citywide strikes of the era, as meetings here helped lead to sweeping changes in labor laws and Women's Rights. It also played a prominent role in the community during the General Slocum and Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire disasters.

Today, 210 E. 5th Street is a quiet residential building.

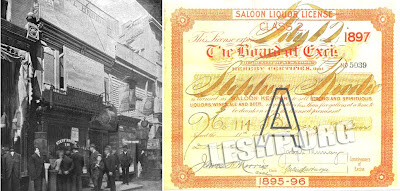

1897 Saloon Locations in the "Jewish Quarter"

Here is a crude map of bar locations in the LES "Jewish Quarter" in 1897. There was one bar for every 208 people living the the neighborhood.

Here is a crude map of bar locations in the LES "Jewish Quarter" in 1897. There was one bar for every 208 people living the the neighborhood.